A recent debate at the European Parliament saw the European Commission and Azorean government representatives question the need for deep-sea mining. Both sides advocated a precautionary approach and stated that critical raw materials would be more effectively addressed through the circular economy.

The January 24th event, ‘Bring deep-sea mining to the surface! Environmental considerations and a need to shed light on decisions’, was hosted by MEPs Linnéa Engström and Marco Affronte. It followed the European Parliament’s adoption of a resolution on international ocean governance, in which it calls for an international moratorium on deep-sea mining exploration and exploitation and asks the Commission and Member States to cease their support for such practices.

Professor Phil Weaver opened with an overview of current knowledge on the environmental risks of deep-sea mining. Mr Bernhard Friess (DG of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries) emphasised the Commission’s commitment to the protection of the deep sea, illustrated by its strong stance on banning deep-sea trawling. Although deep-sea mining is listed as a priority in the EU’s blue growth strategy, Mr Friess reiterated the conclusion of the Joint Research Centre’s report ‘Critical Raw Materials and the Circular Economy’, that the use of critical raw materials is far from fully circular in the EU economy. Many improvement opportunities exist in recycling, re-use, product lifetime extension and new business models. A wider public debate about the need for deep-sea mining is also needed, he said.

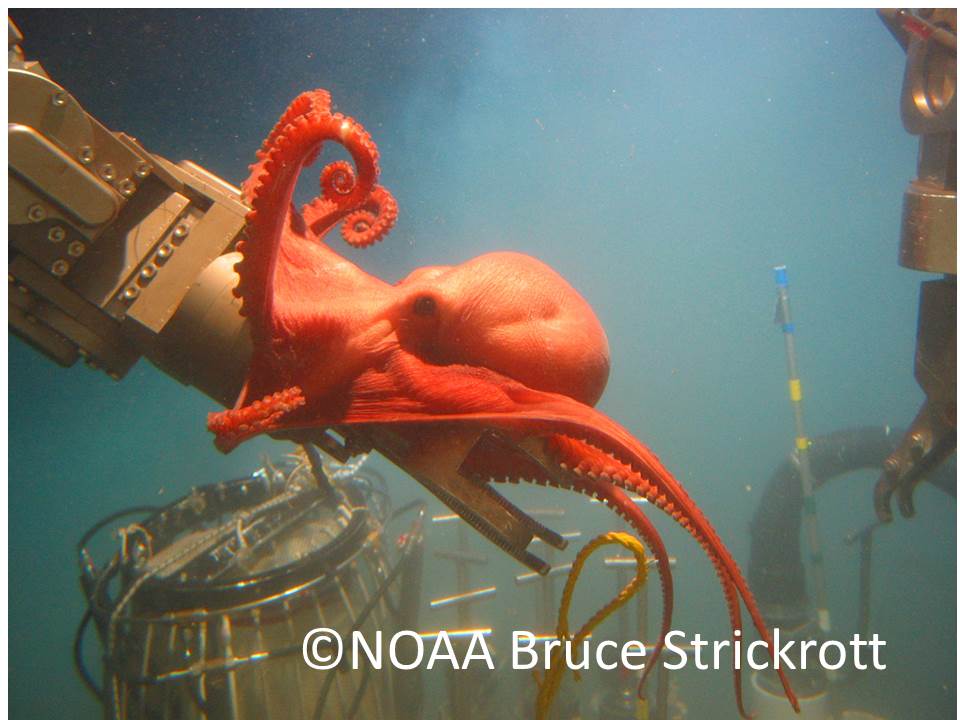

Mr Iván López, Europêche, stated that the deep-sea trawling ban would be undermined if deep-sea mining were to be pursued. He recommended the creation of a scientific and stakeholder forum, similar to the Regional Fisheries Management Organisations. Matt Gianni of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition highlighted the increasing recognition amongst scientists that biodiversity loss would be inevitable if deep-sea mining is permitted to occur. He also called for greater transparency on the part of the International Seabed Authority and its member countries echoing similar provisions in the European Parliament resolution.

Mr Frederico Cardigos, representing the Azores regional government, made an impassioned plea for a precautionary approach to deep-sea mining (the Portuguese government is currently considering a deep sea mining application in Azorean waters by the Canadian company Nautilus). He highlighted the scientific uncertainty about the environmental impact of exploration and exploitation, calling such activity an unacceptable risk. In view of the early stages of EU and Member State action towards a fully implemented circular economy, deep-sea mining will not be necessary in the immediate future, he said. ‘With science, with clarity and with participation, our position might change but – for now – deep-sea mining? No, thank you.’

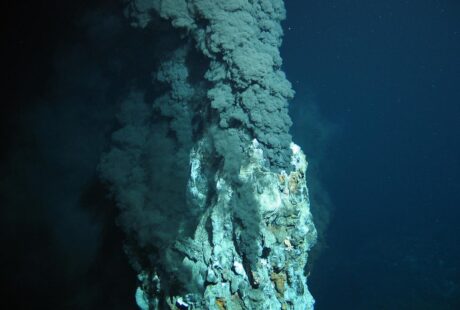

Mr Cardigos went on to draw attention to the Marine Park of the Azores, which encompasses a buffer area around hydrothermal vents in order to protect these vulnerable marine ecosystems from potential deep-sea mining activities. Of this regional ‘red line’, he said, ‘The Marine Park of the Azores, in a sense, is our soul and we are committed to preserving our soul.’

With several participants challenging the need for deep-sea mining, the debate marked a shift away from the prevailing narrative. There was a clear message to the Commission to step back from deep-sea mining as a priority blue growth sector and instead to focus on sustainable use of minerals. A crucial next step is to establish a mechanism for public debate and stakeholder involvement in the EU’s policy development on deep-sea mining.

Posted on: 5 February 2018