(May 31, 2021) – A growing progressive bloc of both developing and developed nations united to insist that the global shipping industry reduce outright emissions this decade to help meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, as the UN’s International Maritime Organisation wrapped up a week of climate talks Friday.

The Intersessional Working Group on Greenhouse Gases (ISWG-GHG) ran through May 24-28. No final agreement was reached on a draft proposal, that could see shipping’s already high emissions of 1 billion tonnes a year of CO2 rise by as much as 16% by 2030.

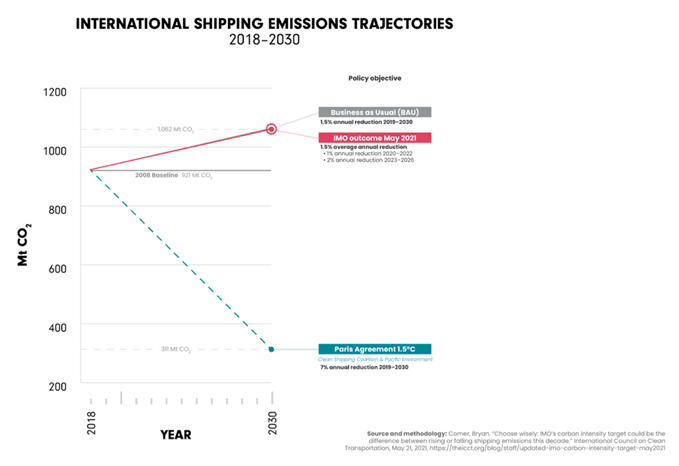

This proposal was resisted by 27 states including the United States, Pacific island nations, and European states, who pushed for targets ambitious enough to peak emissions and set them on a pathway closer to the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 degree C goal (see graph).

This growing progressive bloc of nations will need to fight the low-ambition draft proposal between now and the IMO’s Marine Environmental Protection Committee meeting beginning June 10, and insist on emissions reduction aligned with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C goal.

Background:

Last week, delegates from over 50 countries at IMO were tasked with hammering out the details of how efficiency regulation would apply to all 60,000 or so existing commercial vessels – a crucial part of the climate puzzle, given the long 25-30 year lifespan of ships.

Since 2019, governments have been negotiating a package of “Short-Term” global policies to put in place in order to ensure the shipping industry achieves at least the bare minimum 2030 targets of the IMO’s Initial Greenhouse Gas Strategy, notably: “at least 40%” reduction in the global shipping fleet’s carbon intensity from a 2008 baseline.

The discussions show that the IMO risks failing to align the shipping industry with the Paris Climate Agreement or keep pace with exciting technological progress on decarbonisation in the shipping sector.

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers says retrofitting modern sails on cargo ships and reducing speeds can cut emissions from the shipping industry by up to 40%. Leading shipping companies plan to scale up hydrogen fuel cells on various vessel types in the next few years, and have many zero-emission vessels on the water by 2030.

Instead of seizing the opportunity to drive uptake of these technologies over the next decade and align shipping with the Paris Agreement, the chair’s proposal would set shipping on an efficiency pathway so weak it would allow outright greenhouse gas emissions to keep rising until 2030. It would only reduce carbon intensity 11% by 2026, which averages out to about a 1.5% reduction each year. The IMO’s own analysis shows that this rate of improvement is no better than business as usual.

What happens next?

Governments will meet virtually at the 76th Marine Environment Protection Committee (“MEPC76”) this June 10-17. If nations put into force the policy package debated last week, they will officially have relegated themselves to allowing shipping emissions to continue to rise until 2030 during the decade of climate emergency.

Hope now rests with the 27 nations who refused to vote for last week’s low-ambition package, including the United States, Pacific Island nations, and many European states, to move carbon intensity targets up in ambition.

Posted on: 31 May 2021