A new Alliance of Pacific parliamentarians calls on Pacific leaders to protect its territorial waters from deep-sea mining. Their action sets an example for the EU, which continues to address its deep-sea mining precautionary position exclusively to international waters, largely ignoring deep-sea mining potential in European seas.

The Pacific alliance includes parliamentarians from French Polynesia, Papua New Guinea, Guam, Tuvalu, the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Palau, New Zealand, Fiji and Vanuatu – all countries with neighbouring Exclusive Economic Zones. The alliance highlights the need to suspend deep-sea mining activities in waters under national jurisdiction, while at the same time also supporting a global moratorium.

In the EU, however, the attention of EU policymakers and governments remains focused on international waters, guided by the position in the Commission’s 2030 Biodiversity Strategy that states:

“In international negotiations, the EU should advocate that marine minerals in the international seabed area cannot be exploited before the effects of deep-sea mining on the marine environment, biodiversity and human activities have been sufficiently researched, the risks are understood and the technologies and operational practices are able to demonstrate no serious harm to the environment, in line with the precautionary principle and taking into account the call of the European Parliament”.

In practice this means engaging in related negotiations at the International Seabed Authority, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and an international legally-binding instrument for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

This external focus risks overlooking European seas – even though the 2018 European Parliament resolution on international ocean governance not only called for an international moratorium but asked for a ban on permits for deep-sea mining on Member States’ continental shelves.

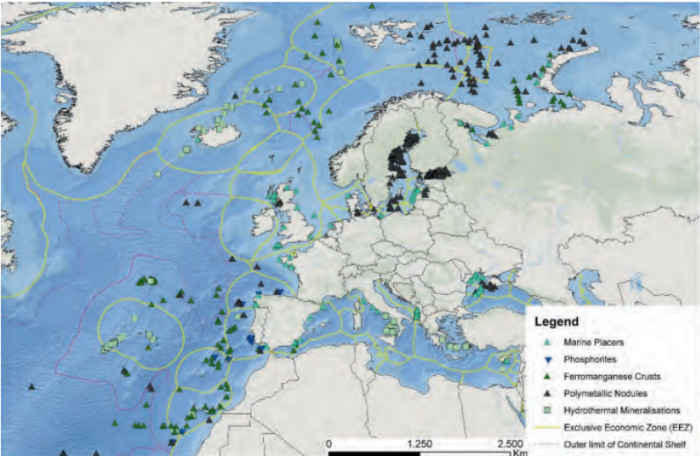

In its 2021 report on the role of Europe in deep-sea mining, Seas At Risk highlighted the potential deep-sea mining threats in European Seas, with several countries asking for extensions of their continental shelves and others engaging in deep-sea exploration. The EU-funded MINDeSEA (Seabed Mineral Deposits in European Seas) project found that most marine mineral occurrences are concentrated in the Arctic Ocean, Baltic Sea, Macaronesia, the Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coasts.

Figure: Marine mineral occurrences in EU waters

Source: The EU Blue Economy Report 2020

Some EU countries, such as Spain and Portugal, have previously signalled their interest in exploring for marine minerals on their continental shelves (around the Canary Islands and Azores respectively). In addition, France seems to be preparing itself for exploitation by defending its exploration rights from a military standpoint. When presenting France’s 2030 investment plan, President Macron stated that deep-sea exploration is a priority, with a focus on France’s overseas departments, French Polynesia, New-Caledonia and Clipperton. Norway has also announced that it may start issuing permits for deep-sea mining exploration on its continental shelf as early as 2023.

Union legislation applies on the continental shelves of Member States, and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive is particularly relevant in this case. The Directive aims to achieve good environmental status for European seas. With its objectives on biodiversity, contaminants, seafloor integrity, food webs, energy, and noise it seems improbable that deep-sea mining could ever be allowed in EU waters.

There are encouraging signs that the 2030 Biodiversity Strategy wording will be adopted at national level. The Spanish Government is the first Member State to take a step towards banning deep-sea mining in its national waters. On 13 April 2022, a Royal Decree defined new criterions for activities carried out in the country’s jurisdiction, aligned with the 2030 Biodiversity Strategy. In Portugal, there was media speculation in 2020 about a moratorium, but no official progress as yet.

Moratorium thinking for territorial waters is more advanced elsewhere in the world. Wallis-et-Futuna (France overseas territory) has proposed a deep-sea mining moratorium in its territorial waters, as has Fiji, backed by Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu, while Australia’s Northern Territory and New South Wales enacted bans in 2021 and 2022.

If the EU aims to be a leader in international ocean governance, it could lead by example and prohibit deep-sea mining in European seas, in addition to supporting a global moratorium. In parallel, it should put in place strong measures to reduce its material footprint, thus making deep-sea mining unnecessary and preventing a terrestrial mining boom. A strong deep-sea protection alliance of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), such as that of the Pacific parliamentarians, could be an important first step.

Posted on: 22 April 2022