The past year has seen growing calls for a moratorium on deep-sea mining. Hundreds of NGOs, the European Parliament, the European fisheries industry and several renowned scientists – including Sir David Attenborough and Sylvia Earle – are recommending precautionary action to protect the deep sea from irreversible large-scale harm. Now, the European Commission has joined the call for such a moratorium

This surprising U-turn can be found in the recently published Biodiversity Strategy, which states:

‘In international negotiations, the EU should advocate that marine minerals in the international seabed area cannot be exploited before the effects of deep-sea mining on the marine environment, biodiversity and human activities have been sufficiently researched, the risks are understood and the technologies and operational practices are able to demonstrate no serious harm to the environment, in line with the precautionary principle and taking into account the call of the European Parliament. In parallel, the EU will continue to fund research on the impact of deep-sea mining activities and on environmentally friendly technologies. The EU should also advocate for more transparency in international bodies, such as the International Seabed Authority.’

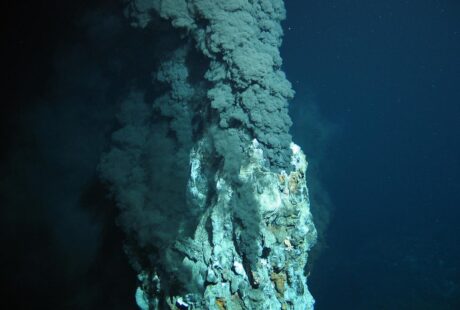

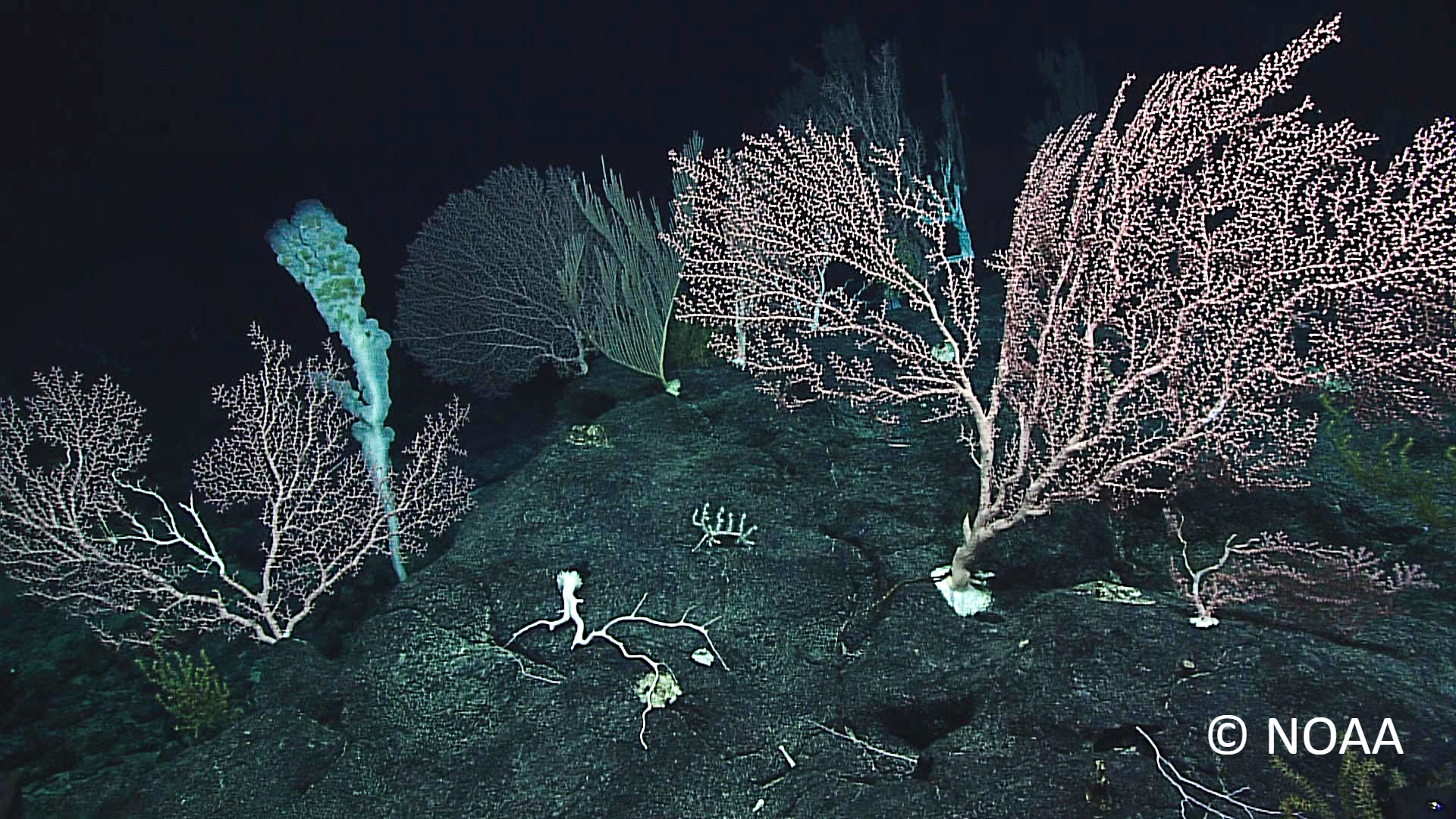

Encouragingly, this new stance on deep sea mining implies a conditional moratorium, although it has not yet been translated into concrete action. Less positive, however, is the suggestion that the Commission intends to continue to fund research into the development of mining technologies, despite the far more urgent need for research into the role of the deep sea ecosystems to mitigate climate change and restore marine biodiversity. The COVID-19 crisis has also put the spotlight on the health solutions that can be found in the deep sea: organisms discovered at extreme depths are used to treat cancer, inflammation, nerve damage and for the detection of COVID-19, among others. Reason the more to protect the deep sea and study its life-sustaining function, instead of mining it.

Since the publication of the Blue Growth Strategy in 2012, the Commission has treated deep-sea mining as a priority blue economy sector, as per the 2019 Blue Economy report. EU research programmes have spent millions of euro developing knowledge on impacts, but also on developing technologies. Deep-sea mining is also promoted under the EU Raw Materials Initiative. By co-funding the MINDeSEA (Seabed Mineral Deposits in European Seas) project the Commission also supports exploration for metals in European seas.

At international level, the EU acts as a ‘silent’ member of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), refraining from taking an active role in the negotiations or from coordinating the positions of EU member states. It does, however, finance an Atlantic Regional Environmental Management Plan Project, in collaboration with the ISA. The Commission also provided financial support to Pacific Island countries to improve the governance and management of their deep-sea minerals resources.

The Biodiversity Strategy’s stance on deep-sea mining is thus a clear break with the Commission’s previous strategies. It partly meets the demand of the Blue Manifesto, in which Seas At Risk and 100+ other NGOs called on the EU to support a global moratorium. Instead of opening up a new frontier of industrial mining in the deep-sea, Seas At Risk advocates for efforts to be channelled into the transition towards less material-intensive economies focused on sustainable consumption and production, sharing economies and changes in lifestyles.

A similar position can be found in the 2019 moratorium demand of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition (DSCC), of which Seas At Risk is a steering member. Other recent moratorium calls have come from the Deep-Sea Mining Campaign and Canada Mining Watch (following their report ‘Predicting the impacts of mining deep sea polymetallic nodules in the Pacific Ocean), WWF International, Greenpeace international and Fauna and Flora International. An overview of the many calls for a moratorium can be found in this DSCC factsheet.

All eyes now turn to the EU and its 27 member states to see the position they will take in the next annual session of the ISA (expected in October 2020), and whether the calls for moratorium will finally be put on the agenda. EU member states play a crucial role at the ISA, as they are all members, have voting rights on regulation, and could request the ISA to consider the many calls for moratorium. Belgium, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Bulgaria, Czechia, Poland and Slovakia are currently sponsoring exploration licences in the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean.

If the EU and its member states are serious about leading international ocean governance, it is time to take the concerns of scientists and civil society to heart and turn the many calls for moratorium into a global reality.

Posted on: 4 June 2020