While the United Nations has concluded that the deep sea contains “the largest source of species and ecosystem diversity on Earth, supporting ecosystem processes necessary for our planet’s natural systems to function”, the European Commission qualifies it as “a new deep sea frontier”. For Ecologistas en Accion, Seas At Risk’s newest member, the term “new [mining] frontier” sets alarm bells ringing as it is widely used for highly speculative mining operations in new territories by those with a taste for high risk investments. It is all too reminiscent of the ‘new mining frontier in Spain’, a current push to open thousands of badly designed, open pit mines. In this article, Ecologistas en Accion reflects on the use of words, the role of the European Commission and Spain, and challenges the extractivism narrative behind it all.

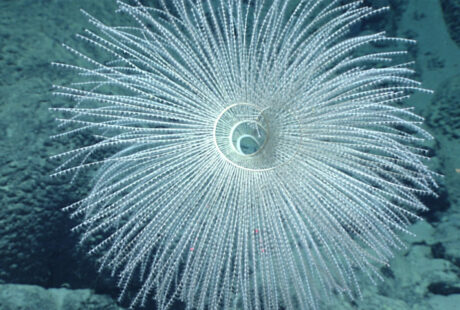

Looking at an image of the Earth taken from space, the first thing one notices is the immensity of the ocean. Its sheer surface size and hidden, deep seabed makes it easy to see the ocean as a space immune to human damage. The collective misconception of the depths of the ocean as a lifeless realm is used as an excuse by those wishing to exploit the natural resources lying beneath the seabed. In this respect, it is interesting that studies and projects funded by the EU have as main objectives: “shedding light on the benefits, drawbacks and knowledge gaps associated with deep sea mining” ; “managing the impact of strategic materials in the European deep sea”; or “assessing the resilience of deep sea ecosystems and biodiversity to resource extraction activities”.

A careful reading of those words makes it obvious that it is not a matter of ascertaining whether or not it is appropriate or sustainable to mine the seabed. Rather, the European Commission has already decided, ignoring the European Parliament, that the deep sea will be mined, without really questioning the need for it. Not only has it transferred public funds to research the impacts of the emerging submarine mining industry, it is increasingly funding technology development.

The projects financed or co-financed by the EU are often led by a cross-border consortia of geologists, mining engineers and companies without any previous marine or land mining experience. These companies, often start-ups, claim to have developed “unique marine technology”, which “harvest” the polymetallic nodules, loaded with cobalt or manganese, covering the seabed as if they were new potatoes.

It is telling that, for instance, the newly launched DeepGreen “state of the art harvester”, does not “drill, blast or dig the bottom of the ocean, but instead, “scoops the nodules up”. Global Sea Mineral Resources, another eager frontrunner, presents itself as ‘specialised in deep sea harvesting’. It all sounds very harmless, like a new and benign form of agriculture. Yet ‘harvesting’ usually refers to crops that can grow back, that can regenerate. The life that deep sea mining will obliterate will never grow back. Scientists have repeatedly warned that deep sea mining would result in irreversible significant biodiversity loss, not only in the exploited areas, but for tens to hundreds of kilometres around, due to the long-distance dispersion of plumes of sediment loaded with toxic particles.

And where exactly is the “new deepsea frontier”? Not only in far removed international waters. Some European countries are interested in exploring seabeds on their continental shelves. Spain, for instance, has formally requested the extension of its continental shelf to the southwest of the Canary Islands to reach an underwater mountain rich in cobalt. There is also an on-going “scientific” campaign to explore the continental shelf off the coast of Malaga, part of the European project Blue Nodules. Such activities are carried out without any administrative or environmental control over their impact on the biodiversity of the seabed or on local economies such as fishing.

Rather than giving away citizens’ money to newly constituted corporate structures, and creating the illusion with carefully picked words that this is a harmless activity, would it not be more reasonable, to stop sea mining explorations until we have a better understanding of the diversity of life and characteristics of the different deep sea ecosystems? And would it not make much more economic and ecological sense to rethink our wasteful extractivist economy, ensuring we make do with the resources we have already extracted, using them wisely instead of wasting them on a vast scale on land? Ecologistas en Accion looks forward to working with Seas At Risk to #KeepItInTheSeabed.

Posted on: 16 July 2019